We changed the name of our chair in 1994 from “Adult Education" to “Andragogik”,

using a term that was coined in 1833 by the German educator Alexander Kapp.

There were mainly three reasons to do this:

- We use the term “andragogy” to label the academic discipline that

reflects and researches the education and learning of adults. By this we

emphasize the differenciation between the field of practice (“adult education”)

and the scholarly approach (“andragogy”).

-

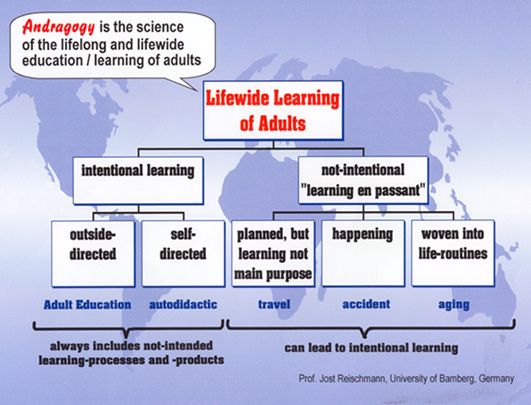

In our understanding “andragogy” comprises the “lifewide learning” of

adults. This understanding includes not only institutionalized forms

of learning, but also selfdirected and even partly-intentional or non-intentional

forms of learning.

- The label "andragogy" gives our graduates a unique label on the job market. This strengthens the identity of our graduates and makes employers curious, what this new profession can add to the needed change processes.

Structural scheme of adult education and adult learning

Autor: Reischmann, Jost (2000): Welcome to ANDRAGOGY.net. At: http://www.andragogy.net. Version Febr. 23, 2000.

Autor: Reischmann, Jost (2004): Andragogy. History, Meaning, Context, Function. At: http://www.andragogy.net. Version Sept. 9, 2004.

The following text (7 pages) can be downloaded (and printed) as .pdf:

Jost Reischmann:

Andragogy. History, Meaning, Context, Function

The term ‘andragogy’ has been used in

different times and countries with various connotations. Nowadays there exist

mainly three understandings:

1. In many countries there is a growing

conception of ‘andragogy’ as the scholarly approach to the learning of adults.

In this connotation andragogy is the science of understanding (= theory)and

supporting (= practice) lifelong and lifewide education of adults.

2. Especially in the USA, ‘andragogy’ in

the tradition of Malcolm Knowles, labels a specific theoretical and practical

approach, based on a humanistic conception of self-directed and autonomous

learners and teachers as facilitators of learning.

3. Widely, an unclear use of andragogy can

be found, with its meaning changing (even in the same publication) from ‘adult

education practice’ or ‘desirable values’ or ‘specific teaching methods,’ to

‘reflections’ or ‘academic discipline’ and/or ‘opposite to childish pedagogy’,

claiming to be ‘something better’ than just ‘Adult Education’.

Terms make sense in relation to the object

they name. Relating the development of the term to the historical context may

explain the differences.

The History of ‘Andragogy’

The first use of the term ‘andragogy’ - as

far as we know today (Poeggeler 1974, p. 19) - was found with the German high school teacher Alexander

Kapp in 1833. In a book entitled ‘Platon’s Erziehungslehre’ (Plato’s

Educational Ideas) he describes the lifelong necessity to learn. Starting with

early childhood he comes on page 241 (of 450) to adulthood with the title ‘Die

Andragogik oder Bildung im maennlichen Alter’ (Andragogy or Education in the

Man’s Age - a replica can be found on www.andragogy.net). In about 60 pages he

argues that education, self-reflection, and educating the character is the

first value in human life. He then refers to vocational education of the

healing profession, soldier, educator, orator, ruler, and men as family father.

So already her we find patterns which repeatedly can be found in the ongoing

history of andragogy: Included and combined are the education of inner,

subjective personality (‘character’) and outer, objective competencies (what

later is discussed under “education vs. training”); and learning happens not

only through teachers, but also through self-reflection and life experience, is

more than ‘teaching adults’.

Kapp does not explain the term Andragogik,

and it is not clear, whether he invented it or whether he borrowed it from

somebody else. He does not develop a theory, but justifies ‘andragogy’ as the

practical necessity of the education of adults. This may be the reason why the

term lay fallow: other terms and ideas were available; the idea of adult

learning was not unusual in that time around 1833,

neither in Europe (enlightenment movement, reading-societies, workers

education, educational work of churches, for example the Kolping-movement), nor

in America (Franklin Institute in Philadelphia, Lowell Institute in Boston,

Lyceum movement, town libraries, museums, agricultural societies); all these

existing initiatives had important dates between 1820-40 and their terminology,

so a new term was not needed.

The Second and Third Invention

In the 1920’s in Germany adult education

became a field of theorizing. Especially a group of scholars from various

subjects, the so-called ‘Hohenrodter Bund’, developed in theory and practice

the ‘Neue Richtung’ (new direction) in adult education. Here some authors gave

a second birth to the term ‘Andragogik’, now describing sets of explicit

reflections related to the why, what for and how of teaching adults.But

Andragogik was not used as “the Method of Teaching Adults”, as Lindeman (1926) mistakenly suggested in reporting his

experiences at the Academy of Labor, Frankfurt, Germany. It was a sophisticated, theory-oriented concept,

being an antonym to ‘demagogy’ - too difficult to handle, not really shared. So

again it was forgotten. But a new object was shining up: a scholarly, academic

reflection level ‘above’ practical adult education. The scholars came from

various disciplines, working in adult education as individuals, not

representing university institutes or disciplines. The idea of adult education

as a discipline was not yet born.

It is not clear where the third wave of

using andragogy originated. In the 1950’s andragogy suddenly can be found in

publications in Switzerland (Hanselmann), Yugoslavia (Ogrizovic), the

Netherlands (ten Have), Germany (Poeggeler). Still the term was known only to

insiders, and was sometimes more oriented to practice, sometimes more to

theory. Perhaps this mirrors the reality of adult education of that time: There

was no or little formal training for adult educators, some limited theoretical

knowledge, no institutionalized continuity of developing such a knowledge, and

no academic course of study. In this reality ‘Adult Education’ still described

a unclear mixture of practice, commitment, ideologies, reflections, theories,

mostly local institutions, and some academic involvement of individuals. As the

reality was unclear, the term could not be any clearer. But the now increasing

and shared use of the term signaled, that a new differentiation between ‘doing’

and ‘reflecting’ was developing, perhaps needing a separating term.

Andragogy: A banner for identity

The great times of the term ‘andragogy’ for

the English-speaking adult education world came with Malcolm Knowles, a leading

scholar of adult education in the USA. He describes

his encounter with the term:

‘… in 1967 I had an

experience that made it all come together. A Yugoslavian adult educator, Dusan

Savicevic, participated in a summer session I was conducting at Boston

University. At the end of it he came up to me with his eyes sparkling and said,

‘Malcolm, you are preaching and practicing andragogy.’ I replied, ‘Whatagogy?’

because I had never heard the term before. He explained that the term had been

coined by a teacher in a German grammar school, Alexander Kapp, in 1833 … The

term lay fallow until it was once more introduced by a German social scientist,

Eugen Rosenstock, in 1921, but it did not receive general recognition. Then in

1957 a German teacher, Franz Poggeler, published a book, Introduction into Andragogy: Basic issues in Adult Education, and

this term was then picked up by adult educators in Germany, Austria, the

Netherlands, and Yugoslavia …’ (Knowles 1989, p. 79).

Knowles published his first article (1968) about

his understanding of andragogy with the provocative title ‘Andragogy, Not

Pedagogy.’ In a short time the term andragogy, now intimately

connected to Knowles’ concept, received general recognition throughout North

America and other English speaking countries; ‘within North America, no view of

teaching adults is more widely known, or more enthusiastically embraced, than

Knowles’ description of andragogy’ (Pratt & Ass., 1998, p. 13).

Knowles’ concept of andragogy - ‘the art

and science of helping adults learn’ - ‘is built upon two central, defining

attributes: First, a conception of learners as self-directed and autonomous;

and second, a conception of the role of the teacher as facilitator of learning

rather than presenter of content’ (Pratt & Ass., 1998, p. 12), emphasizing

learner choice more than expert control. Both attributes fit into the specific

socio-historic thoughts in and after the 1970’s, for example the deschooling

theory (Illich, Reimer), Rogers person-centered approach, Freire’s

‘conscientizacao’. Perhaps a third attribute added to the attraction of Knowles

concept: Constructing andragogy as opposing pedagogy (“Farewell to Pedagogy”, 1970) (later reduced) provided

opportunity to be on the ‘good side,’ not a

‘pedagogue,’ seen as ‘a teacher, especially a pedantic one’ (Webster’s

Dictionary, 1982, p. 441). This flattered adult educators in a time, where most

adult educators were andragogical amateurs, doing adult education based on

their content expertise, experience, and a mission they felt, not based on

trained or studied educational competence. To be offered now understandable,

humanistic values and beliefs, some specific methods and a good sounding label,

strengthened a group that felt inferior to comparable professions. And this

came coincidentally along with a significant growth of the field of practice

plus an increased scholarly approach, including the emerging possibility to

study adult education at universities. All these elements document a new period

(‘art and science’) in adult education; it made sense to concentrate this new

understanding in a new term.

Providing a unifying idea and identity,

connected with the term andragogy, to the amorphous group of adult educators,

certainly was the main benefit Knowles awarded to the field of adult education

at that time. Another was that he strengthened the already existing scholarly access

to adult education by publishing, theorizing, doing research, by educating

students that themselves through academic research became scholars, and by

explicitly defining andragogy as science (Cooper & Henschke, 2003).

Issues with Andragogy

Over the years

critique developed against Knowles’ understanding of andragogy. A first

critique argues that Knowles claimed to offer a general concept of adult

education, but like all educational theories in history it is but one concept,

born into a specific historic context. For example, one of Knowles’ basic

assumptions is that becoming adult means becoming self-directed. But other

genuine concepts of adult education do not accept this ‘American’ type of

self-directed lonesome fighter as the ultimate

educational goal: In family, church, or civic education, for instance, the ‘we’

is more important than the ‘self’. Similarly an instructor who presents (=teaches)

the name of the stars in a hobby-astronomy class would not work andragogical

because this is not autonomous learning. Consequently the Dutch scholar van

Gent (1996) criticizes, that the

andragogy concept of Knowles is not a general-descriptive, but a ‘specific,

prescriptive approach’ (p. 116). Another

critique is Knowles’ conceiving of pedagogy as pedantic schoolmasters’

practice, not as an academic discipline. This hostility toward pedagogy had two

negative outcomes: On a strategic level, scholars of adult education could make

no alliances with the colleagues from pedagogy; on a content level, knowledge

developed in pedagogy through 400 years could not be made fruitful for

andragogy (more critical remarks see Merriam/Caffarella, 1999, p. 273ff,

Savicevic, 1999, p. 113ff). Thus, attaching ‘andragogy’ exclusively to

Knowles’ specific approach means that the term is lost for including

pedagogical knowledge and those who do not share Knowles’ specific approach.

The European development:

towards Professionalisation

In most countries of Europe the Knowles-discussion played no or at

best a marginal role. The use and development of ‘andragogy’ in the different

countries and languages was more hidden, disperse, and uncoordinated, yet

steady. ‘Andragogy’ nowhere described one specific concept or movement, but

was, from 1970 on, connected with the in existence coming academic and

professional institutions, publications, programs, triggered by a similar

growth of adult education in practice and theory as in the USA. ‘Andragogy’

functioned here as a header for (places of) systematic reflections, parallel to

other academic headers like ‘biology’, ‘medicine’, ‘physics’. Examples of this

use of andragogy are

the Yugoslavian (scholarly) journal for

adult education, named ‘Andragogija’ in 1969; and the ‘Yugoslavian Society for

Andragogy’;

at Palacky University in Olomouc (Czech republic) in 1990 the “Katedra sociologie a andragogiky” was established,

managed by Vladimir Jochmann, who advanced the use of the term “andragogy”

(andragogika) against “adult education” (“Vychova a vzdelavani dospelych”),

which was discredited by communistic use. Also Prague University has a ‘Katedra

Andragogiky’;

in 1993, Slovenia’s ‘Andragoski Center

Republike Slovenije’ was founded with the journal ‘Andragoska Spoznanja’;

in 1995, Bamberg University (Germany) named

a ‘Lehrstuhl Andragogik’; the Internet address of the Estonian adult

education society is ‘andra.ee’.

On this formal level ‘above practice’ and

specific approaches, the term andragogy could be used in communistic countries

as well as in capitalistic, relating to all types of theories, for reflection,

analysis, training, in person-oriented programs as well as human resource

development.

A similar professional and academic

expansion developed worldwide, sometimes using more or less demonstratively the

term andragogy: Venezuela has the ‘Instituto Internacional de Andragogia’,

since 1998 the Adult & Continuing Education Society of Korea publishes the

journal ‘Andragogy today’. This documents a reality with new types of

professional institutions, functions, roles, with fulltime employed and

academically trained professionals. Some of the new professional institutions

use the term andragogy - meaning the same as ‘adult education’, but sounding

more demanding, science-based. Yet, throughout Europe still ‘adult education’,

‘further education’ or ‘adult pedagogy’ is used more than ‘andragogy’.

Adult education or education of adults?

Some writers limit andragogy to a teaching

situation (or more in the jargon: helping-adults-learn situation). An early

example is Lindeman (1926), when reporting

from his experiences at the Academy of Labor, Frankfurt, Germany: he connects

Andragogik (using the German term) with teaching by giving his article the

title ‘Andragogik: The Method of Teaching Adults’. Knowles, who brought the

Americanized version “andragogy” into discussion, also uses this limiting

understanding: ‘Andragogy is the art and science of teaching adults’. This

definition is generalized by Krajinc (1989, p. 19) from Slovenia in a British

international handbook: “Andragogy has been defined as…’the art and science of

helping adults learn and the study of adult education theory, processes, and

technology to that end’.’

Other authors include

‘education and learning of adults in all its forms of

expression’ (Savicevic, 1999, p. 97). Reischmann (2003) offers the term

‘lifewide education’ to describe the opening of this new field, thus

encompassing formal and informal,

intentional and ‘en passant’, institution-supplied and autodidactic learning.

These differences in understanding have to

be seen in a historic development of the perception of ‘adult education’: What

was perceived as ‘adult education’ in 1833 or 1926 is different from 1969 or

2001. While until the 1970’s the interest in adult education was focused on the

action-oriented questions “How can teachers/facilitators support the learning

of adults?”, now a new, more analytical-descriptive perspective was added. From

the 1970’s on it was more and more perceived and discussed, that learning of

adults did not only happen in more or less institutionalized or traditional

settings, arranged specifically for the learning of adults. In North America

Allen Tough’s research about adult learning projects provided evidence that

only the ‘tip of the iceberg’ of adults learning was ‘adult education’. In

Germany the perception of learning in social movements like self-help groups or

citizen-initiatives (peace-movement, feminist groups) started the discussion

about the ‘Entgrenzung’ (de-bordering) of adult education. Distance- and

E-learning, assessment of prior learning, learning in non-traditional forms,

life-situations as learning opportunity, and other non-school-oriented forms and situations where adults learn widened the

perception that the education of adults happen in more situations than just in

adult education.

As a consequence today many experts understand “adult education” only as a segment of the wider field of the education of adults.

Andragogy: Academic discipline

Besides

this widened perception of adult learning another development challenged the

understanding of ‘adult education’ in the last decades: The field of adult

education worldwide went through a process of growth and differentiation, in

which a scholarly, scientific approach emerged. And a new type of ‘adult

educators’ was born, which was not qualified by their missions and visions, but

by their academic studies. And writing a thesis or dissertation is a quite

different task than educating adults: reflection, critique, analysis,

historical knowledge qualified this new type of academic professionals.

An academic discipline with university

programs, professors, students, focusing on the education of adults, exists

today in many countries. But in the membership-list of the Commission of

Professors of Adult Education of the USA (2003) not one university institute

uses the name ‘andragogy’, in Germany one out of 35, in Eastern Europe six out

of 26. Many actors in the field seem not to need a label ‘andragogy’. However,

other scholars, for example Dusan Savicevic, who provided Knowles with the term

andragogy, explicitly claim ‘andragogy as a discipline, the subject of which is

the study of education and learning of adults in all its forms of expression’

(Savicevic, 1999, p. 97, similarly Henschke 2003, Reischmann 2003). This claim is not a

mere definition, but includes the prospective function to influence the coming

reality: to challenge ‘outside’ (demanding a respected discipline in the

university context), to confront ‘inside’ (challenging the colleagues to clarify

their understanding and consensus of their function and science), overall to

stand up to a self-confident academic identity.

Again here this

claim only makes sense when an object exists worth to get labeled. Not the term

makes a (sub-) discipline, but a reality with sound university programs,

professors, research, disciplinarian knowledge, and students. If, where and when

this exists, a clarifying label like “andragogy” will make sense.The coming

reality will show whether the ongoing differentiation in institutions,

functions, and roles will need a term ‘andragogy’ for conceptual clarification.

References and Further Reading

- Gent, van, Bastian (21996): ‘Andragogy’. In: A. C.

Tuijnman (ed.): International Encyclopedia of Adult Education and Training.

Oxford: Pergamon, p. 114-117.

- Cooper, Mary K. & Henschke, John

A. (2003): An Update on Andragogy: The International Foundation for Its

Research, Theory and Practice (Paper presented at the CPAE Conference, Detroit,

Michigan, November, 2003).

- Henschke, John (2003): Andragogy Website http://www.umsl.edu/~henschke

- Jarvis, Peter (1987): Towards a discipline of adult education?, in

P. Jarvis (ed): Twentieth Century Thinkers in Adult Education. London:

Routledge, p. 301-313.

- Kapp, Alexander (1833): Platon’s Erziehungslehre,

als Paedagogik für die Einzelnen und als Staatspaedagogik. Minden und Leipzig:

Ferdinand Essmann.

- Knowles, Malcolm S. (21978): The Adult Learner: A Neglected Species. Houston: Gulf Publishing Company.

- Knowles, Malcolm S. (1989): The Making of an Adult Educator. San

Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Krajinc, Anna

(1989): Andragogy. In C. J. Titmus (ed.): Lifelong Education for Adults: An International

Handbook. Oxford: Pergamon, p. 19-21.

- Lindeman, Edward C. (1926). Andragogik: The Method of Teaching

Adults. Workers’ Education, 4: 38.

- Merriam, Sharan H. and Caffarella, Rosemary S. (21999): Learning in Adulthood. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Poeggeler, Franz (1957): Einfuehrung in die Andragogik. Grundfragen der Erwachsenenbildung. Ratingen: Henn Verlag.

- Poeggeler, Franz (1974): Einführung in die Andragogik – Grundfragen der Erwachsenenbildung. (Handbuch der Erwachsenenbildung Band 1). Stuttgart: Kohlhammer.

- Pratt, Daniel D., & Associates

(1998): Five perspectives on teaching in adult and higher education. Malabar, FL: Krieger.

- Reischmann, Jost (2003): Why Andragogy?

Bamberg University,

Germany http://www.andragogy.net.

- Savicevic, Dusan (1991): Modern

Conceptions of Andragogy: A European Framework. In: Studies in the Education of

Adults, Vol. 23, No. 2, p. 179-191.

- Savicevic, Dusan (1999): Understanding Andragogy in Europe and

America: Comparing and Contrasting. In: Reischmann, Jost/ Bron, Michal/ Jelenc,

Zoran (eds): Comparative Adult Education 1998: the Contribution of ISCAE to an

Emerging Field of Study. Ljubljana, Slovenia: Slovenian Institute for Adult

Education, p. 97-119.

- Tough, Allen (21979): The Adult’s Learning Projects. Toronto: The Ontario Institute for Studies in Education.

- Webbster’s New World Dictionary of

the American Language (1982). New York: Warner Books.

- Zmeyov, Serguey (1998): Andragogy: Origins, Developments, Trends. In: International Review of Education. Vol. 44, No. 1, p. 103-108.

Autor: Reischmann, Jost (2004): Andragogy. History, Meaning, Context, Function. At: http://www.andragogy.net. Version Sept. 9, 2004.

Jost Reischmann is Professor of Andragogy (retired) at Bamberg University in Germany. He is President of the International Society

for Comparative Adult Education (ISCAE) and member of the International Adult

and Continuing Education Hall of Fame.

Since February 22, 2000, we counted

visitors to this page.